This is the second part of a guest post by Andy Murray of Ragged Theology. Challenging and thought-provoking stuff as ever.

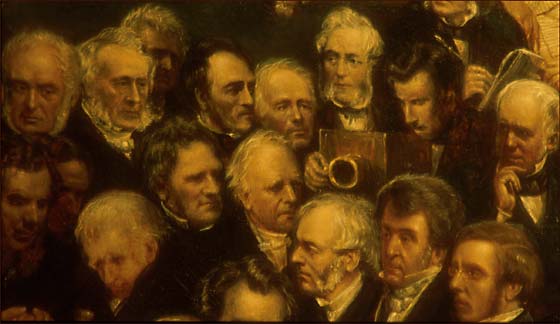

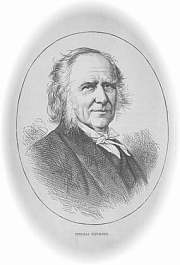

Men like Thomas Guthrie and William Wilberforce inspired a movement rooted firmly in Micah 6 v 8. They called the church and nation to love justice, show mercy and walk humbly with the God of the Bible. They wrote, they spoke, they preached, they persuaded and they campaigned for change to the way the poor were treated. The work went on long after they were dead. Their work changed whole communities, changed laws and changed the direction of our nation. When Guthrie died in 1873 not only was education about to be offered to all, but thanks to Christian social reformers children were finally being offered protection and care instead of exploitation. Men like Guthrie and Wilberforce were hated and opposed because they challenged the powerful vested interests in the alcohol and slave industries respectively. But through all the challenges, they had an unquenchable hope in the redeeming gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ. A hope that the most visionary and noble secularist cannot offer. This is why secularism soon turns to pessimism. As Blaikie says:

Secularism may try to keep up its spirits, it may imagine a happy future, it may revel in a dream of a golden age. But as it builds its castle in the air, its neighbour, Pessimism, will make short and rude work of the flimsy edifice. Say what you will, and do what you may, says Pessimism, the ship is drifting inevitably on the rocks. Your dream that one day selfishness will be overcome, are the phantoms of a misguided imagination; your notion that abundance of light is all that is needed to cure the evils of society, is like the fancy of keeping back the Atlantic with a mop. If you really understood the problem, you would see that the moral disorder of the world is infinitely too deep for any human remedy to remove it; and, since we know of no other, there is nothing for us but to flounder on from one blunder to another, and from one crime to another, till mankind works out its own extinction; or, happy catastrophe! The globe on which we dwell is shattered by collision with some other planet, or drawn into the furnace of the sin.

It is the Christian gospel that has been the great agent of change in human history. Has the church at times been corrupt? Absolutely. Has it at times disregarded the poor and even abused them. Unfortunately, it has. But what has been the fruit of the revival of true Christianity? It has always been love, particularly for the poor. The spirit of self-seeking is supplanted by the spirit of service and love. Vice is replaced by virtue. When men love God in sincerity, they will love their neighbour, particularly the poor and the outcast. The church at its best lives by that early ‘mission statement’ in James 1 v 27 ‘Religion that is pure and undefiled before God the Father is this: to visit orphans and widows in their affliction, and to keep oneself unstained from the world.’ As Thomas Guthrie said about the kind of Christianity that brings transformation to communities;

We want a religion that, not dressed for Sundays and walking on stilts, descends into common and everyday life; is friendly, not selfish; courteous, not boorish; generous, not miserly; sanctified, not sour; that loves justice more than gain; and fears God more than man; to quote another’s words – “a religion that keeps husbands from being spiteful, or wives fretful; that keeps mothers patient, and children pleasant; that bears heavily not only on the ‘exceeding sinfulness of sin,’ but on the exceeding rascality of lying and stealing; that banishes small measures from counters, sand from sugar, and water from milk-cans – the faith, in short, whose root is in Christ, and whose fruit is works.